- Home

- Kristee Ravan

The Cinderella Theorem Page 10

The Cinderella Theorem Read online

Page 10

“Hey. Aren’t you supposed to be teaching me all that? Or are you too busy running around trying to have the best record?”

Calo scowled again.

I continued, “Yes, I am constantly aware, mostly thanks to you, that I know virtually nothing about this world, and I know that variable significantly subtracts from my success here. But, I am more than willing to learn. The question is, Mr. Perfect Happiologist, are you willing to teach me? Because I don’t see any other way out of this situation.”

“Did you complete the survey?” Calo sat down at his desk.

“What?” I asked, again–this time because I felt Calo’s question was an inappropriate response to my rant.

“The survey I sent. Did you finish it?” Calo calmly pointed to the file folder in my hand, in case I still had no idea what he was talking about.

“Oh,” I said, looking at the folder. “Yeah. Here.” I gave the whole stupid file to him.

“Thank you,” he said, handing me a blank diagram of the Happiness Monitor. “Fill this out.” He turned back to his desk and began reading my survey answers.

I went to my desk and started filling in the diagram’s blanks. Luckily, I have a good memory, especially if I can apply a mnemonic device. I finished the “quiz” in two minutes. Calo looked up when I handed it to him.

“You’re finished already?” He looked skeptical.

I nodded, trying to look annoyingly sweet.

“Alright. Let’s see.” He grinned smugly as he grabbed a red pen from his desk and began grading. The pen was poised to point out any error, but he got to the end of the diagram without marking anything. He looked slightly puzzled; then he began checking the diagram again. I smiled with (at the very least) equal smugness. Score one for Lily.

After a few more minutes of checking and rechecking, Calo finally put the pen down. “So you’ve memorized the different levels of the Monitor.”

“Just like you asked me to.” I smiled.

“It’s just too bad you didn’t do what I asked yesterday at Morgan’s.”

I opened my mouth to argue.

“Anyway,” Calo went on, ignoring me. “Today, we’re going over the Happiness Monitor–its history, uses, what the levels mean, etc.” He put an hourglass monitor on my desk. It was full of white liquid. “Now, you were given a monitor of your own at your presentation, correct?”

“Yes, but mine has plaid liquid in it.”

“Right,” Calo grabbed a three-ring binder and started flipping through it. “That’s because your fairy godmother is Glenni. Her trademark is plaid. All of the godchildren in her care have plaid-filled monitors. I, like most of us, don’t have a fairy godmother catering to my every whim, so I have white liquid in my monitor.” He pointed to the one on my desk.

“Wait a minute,” I interrupted. “Your monitor? You have one?”

“Yes, Lily,” Calo said, exasperated. “Everyone has one. Section 4G of the Mandamus of Happiness.” He put the binder away, got down on his hands and knees, and crawled under his desk. “And I quote: ‘Every resident of E. G. Smythe’s Salty Fire Land,” (His voice was muffled and he had completely disappeared under the desk.) “whether of fictional or natural creation, shall employ and retain a Happiness Monitor in the Office of Happily Ever After Affairs.’ End quote.” He came out from under the desk pushing a poster board in front of him.

“‘Fictional or natural creation?’”

Calo pulled an easel out from behind his desk and placed the poster board on it. It was a giant diagram of a Happiness Monitor. “Right. ‘Fictional creation’ refers to the citizens from stories. Naturally created citizens are the ones like your family and Grimm—people who have been invited to live here.”

“Oh.” I mentally sorted fictional and natural citizens into a table. “Which are you?”

Calo looked at me for a moment. I thought he was about to say something typically rude and grumpy, but he just said, “Fictional. Fairy Tale, actually.”

“Really? Which one?” I was a little interested, not because I’d know which story he would be talking about, but because it seemed like something you should know about one of your fictionally created friends. Corrie is a naturally created friend, and I know her parents and about her background. Her dad is Irish and her mom is Italian. (Although, it is possible that Calo doesn’t satisfy the equation of “friend.”)

“Puss-in-Boots.”

“Is that the one about the magic beans?”

“Uh...no. That’s Jack and the Beanstalk. Puss-in-Boots is the talking cat. Kills the ogre for his master, you know.”

I didn’t know, but that wasn’t the pressing point. “You’re not a cat.”

“Well, you are observant.” Typical Calo. “No, I’m not a cat. But I am a second son.”

“And?” Calo’s hints are about as easy to figure out as trying to plot a line with only one set of coordinates.

He sighed. “How you can know so little is beyond me. In my story, my father dies. He left the mill–you do know what a mill is, right?”

“Yes.” I’m not a moron.

“Good.” He sighed in mock relief. “Anyway, Dad left the mill to my older brother, and he left the cat, which happened to be talking (though we didn’t know it at the time) to my younger brother. And I, being the second son, was left my father’s coat and hat. My older brother and I didn’t get along so well, so I decided to make my way in the world.”

“That doesn’t seem very fair.”

“Well, technically, the fairy tale is just about the youngest son. In the actual text, my older brother and I are only in the first paragraph. But since we were fictionally created–here we are.” He pointed to the hourglass on my desk. “Citizens who must have their Happiness monitored.”

I looked at Calo’s monitor. All the measuring liquid was in the bottom half of the hourglass. Under the Happy line. “You’re unhappy.”

“No, I’m not Unhappy. You vanish when you’re Unhappy, and yet I am still here. I’m Less Than Less Than Happy. There’s a difference.”

“Oh.”

Calo pointed to the Less Than Less Than Happy line on the poster. “This is where I am. Less Than Less Than Happy is an acceptable state of happiness. People are not always going to be Happy from day to day. Fluctuations are expected. However,” he pointed to the line below Less Than Less Than Happy, “at the Could be Happier Level, we, here at HEA, begin to be concerned.”

“Why?” Could be Happier was still four lines away from Unhappy. “It seems a little far from the vanishing point.”

“It is a safety measure. We send out Happiologists at Could be Happier, because a person who Could be Happier is easier to cheer than a person who’s Been a Lot Happier,” he pointed to that level on the diagram, “Or a person who’s Not so Happy.” The Not so Happy level was the one right above Unhappy.

That makes sense, oddly enough. Well, as much sense as measuring Happiness can. “So when a person’s monitor shows that they Could be Happier, a Happiologist goes out and tries to cheer them back up to the Less Than Less Than Happy line?”

“Negative.” Calo pointed to the Happy line in the exact middle of the hourglass. “When a person is being cheered, their level must go up to Happy before the case is closed. A Happiologist stays with that case until the person can maintain happiness for three days. I mean, people are supposed to be living Happily Ever After here, not Could be Happier Ever After. And they’re less likely to have a relapse if we get them to Happy. Did you get all that?”

I nodded. The monitor is like a number line. (I love finding math in random places!)

“Great.” Calo took a sheet of paper off his desk and gave it to me. “This is the latest update–the three o’clock one. Doug’ll be bringing the four o’clock pretty soon.”

I looked at the clock: it was 3:53. “Doug?”

“He’s Head Observer up in The Observatory. Observers make sure that Happiologists get hourly reports on Happiness levels.” Calo pointed at

the paper. “Glance over that and tell me who we should be concerned about.”

I did not glance at it. Mathematicians rarely glance; the margin of error is greatly increased if you are only quickly looking at something. I examined the paper. The first thing I noticed was that it was only one page.

“This can’t be everyone.” I said, matter-of-factly. “There are only twenty-five names on here.” I looked at Calo. I’m certainly not claiming to know everyone in this story world come true, but I think I could now name more than twenty-five.

“Oh, right.” Calo sat on his desk. “Each Happiologist just gets one page of the list, just their clients. Some of the characters rotate around each month, and some stay with the same Happiologist. For instance, King Arthur and Morgan Le Faye are regulars for me.”

“Who decides if they become a regular?”

“The characters themselves. They mail in a card at the end of the month indicating their choice for the next month. It’s a pretty reliable system. That way they can find the Happiologist that works best with them. You don’t want to mess around with Unhappiness if things aren’t working out between you and your client.”

“So they just shop around?”

“Some do. Some don’t. Some like the change, and some want a steady relationship.”

I saw a lot of problems with this “reliable” system. What if a character, who liked to switch around, kept switching, but with each passing month the character’s Happiness level dropped a little. How would the Happiologists be able to recognize the problem? Also, if a character got into a destructive pattern, it wouldn’t be hard to–I stopped myself.

Why am I considering potential problems at HEA? I sighed. Against all mathematical reasoning, this place is becoming normal to me. And that is not normal.

I returned to examining Calo’s portion of the list. On the left hand side, the names of the characters were listed and on the right, their corresponding levels of happiness. Calo had asked me to point out potential problems with citizens. That meant that I was looking for levels of Could be Happier and lower. I looked down the list.

The first name was Minerva (Goddess of Wisdom). She wasn’t a problem at More Happy Than Usual. Both Hugo Wolf (The Big Bad Wolf) and King Arthur were Less Than Happy. Sirena (The Little Mermaid) was Averagely Happy, and Morgan Le Faye, at Rather Happy, still seemed to be delighting in the memory of vanishing me.

Near the middle of the page, I found my first Could be Happier–Baile (Third of The Twelve Dancing Princesses). I made a mental note and continued my examination. Two names below Baile, Amphi (The Frog Princess) had Been Happier, and Sula Gansa (The Goose Girl) Could be Happier. The rest of the names on the list were Less Than Less Than Happy or happier.

I returned the list to Calo. “Baile, Amphi, and Sula Gansa are at risk. Amphi’s risk is compounded by her being at the Been Happier level.”

“Right.” Calo handed me a green highlighter. “Your first job, when you come in to work, will be to take any hourly reports on your desk and highlight those we should be concerned about. I’ll take care of the ones that come in while you’re at school.” Calo glanced at the clock; it was exactly four. “Ah,” he said, turning to the bald man who appeared at the entrance of our cubicle, “right on time, as usual, Doug. Thank you.” He took the four o’clock update from Doug and handed it to me. “Happy highlighting, Lily.”

~~~

Wednesday and Thursday were spent at school (where there was not enough math), at work (where there was even less math), and at home (where there was plenty of math to be had–if I could get away from my parents to do it). Since Mom and King Tub Man both stopped working before supper, they wanted the “family” to spend the evening together in the living room. They also wanted the “family” to contribute to “family discussions” at “family dinners,” which were all catered by Lubcker and company.

I discovered on Tuesday night another lie must be added to my mother’s portfolio. It seems she can’t cook at all. Apparently, Lubcker would bring supper over while I was still at school. Mom would heat it up, serve it to me, and claim it was hers. Mom was a little offended when I pointed out my whole childhood had been a lie.

“I don’t see what the big deal is, Lily. It’s not like you were malnourished.”[33]

Work continued in its normal, Smythian way. Calo treated me like a child, making disbelieving noises when I asked questions he felt I should already know the answer to or openly mocking any ideas I had.

On Wednesday, during our review of case histories, I suggested that we make a chart to organize our data. Specifically, I was looking at Sirena’s file. Since, as a mermaid, she lives in the ocean, I thought it would be to our advantage to examine tidal patterns and sea temperature trends and their effect on her Happiness. Calo did not agree.

“Because that would affect her Happiness how exactly?” He scowled. “She spends over half her time in her human form–on land.”

“Suppose she likes to swim (as a mermaid or as a human) in a certain shallow area. She wouldn’t be able to swim when the tide went back out, or—”

Calo interrupted. “That’s stupid. Sirena likes things to do with humans. All you have to do is give her a fork or a sewing kit, and it raises her level. Once I gave her a set of water wing floaties and she went straight to Excessively Happy.”

“But that doesn’t fully address the problem, you need—”

“Yes, it does. The problem is that she is Unhappy. The solution is to make her Happy. Hammers and hand mixers will do that.”

“But that doesn’t tell us why she’s unhappy. If we don’t figure that out, we’ll never be able to help her. The charts could—”

“Take up unnecessary time.” He interrupted and annoyingly finished my sentence. “While we’re out there measuring the sea’s temperature and charting tidal fluctuations, she’d be getting unhappier and closer to vanishing. If we don’t prevent her vanishing, then we’ll lose her story. Which, to me, is far worse than never knowing the exact reason why she’s unhappy in the first place.” He stomped out of the cubicle, which was fine with me.

On Thursday afternoon, however, I had no extra time to consider revolutionizing HEA. Calo kept all parts of my mind occupied in solving hypothetical situations. They were basically cases in which you would figure out everything you would do to solve the case, without actually solving it.

Calo played the citizens and I, of course, was the Happiologist. He was especially entertaining as Potio Bane, pretending that his crop of apples had been sat upon by Jack’s giant. I think I did fairly well at making the fake people happy.

Solving cases involved looking at the case file, reading the story to brush up on familiarity (or, in my case, to learn anything at all about the story), and reviewing past cases to see what other Happiologists have found successful.

Calo seemed pleased with my progress. As I got on my bike after work, he said, “I think you’re ready for some practice on an actual citizen. See you tomorrow, Lily.”

There was some satisfaction in my smile as I rode back to the castle.

~~~

Kelly Stewart poked me in the back. “Pay attention!” She hissed.

“Lily?!” Mrs. Fox looked at me. “Did you hear my question?!”

“Uh...no, Mrs. Fox, I didn’t.” Once again, Legendary Literature had failed to hold my interest.

“Well! I’ll ask it again!” Mrs. Fox bounced ever so slightly on the balls of her feet, completely the image of a living exclamation mark. “Will you read the handout please?!”

When did we get a hand out? I looked at my desk. Not only did I have the handout, but I had already covered the margins with algebra problems.

I read, “‘As a body of work, legendary tales are ignored by some students of literature. They feel that their oral beginnings lead to questionable, even laughable holes in the plot lines. These critics feel that the improbabilities of most of the plots in legendary literature reflect a simple culture, a time long pas

sed, and a people inferior to modern man. But are they right?

“‘You must decide. You may choose either argument: ‘Legendary Literature is worthy of study’ or ‘Legendary Literature is not worthy of study.’ You will write a three-page paper arguing your position with examples. For instance, if you feel that the oral nature of the tales makes them unreliable, then you will include examples of stories in your paper whose plots have suffered because they were not originally written down. Topics will be due on Monday and the papers on September 13.’”

“Thank you, Lily! That means you’ll have two weeks to write your papers! Don’t put them off until the last minute!” The bell interrupted. “Have a good weekend! Don’t forget to have your topic ready on Monday!”

A whole paper about fairy tales? Ugh. We do not do enough math-related work in this school.

~~~

I had just finished highlighting potentially unhappy citizens (there were five today), when Calo walked in and glanced over the list.

“Hmm. No change then.” He dropped a file folder on my desk. “Okay, Lily,” he said, cheerily. “King Arthur has kindly agreed to let you practice on him this afternoon.”

“He’s not in danger. He’s only Less Than Happy.”

Calo looked at me funny, looked at the update, looked at me again, and said, “How did you know that?”

I shrugged. “I’ve got a good memory.”

“Clearly.” Calo appeared for a moment to be about to say something else, but then he shook his head slightly. “Right. He’s only Less Than Happy, which technically isn’t in danger, but it also isn’t Happy. I need you to have some practice with cases that uh…” He stopped and seemed to be trying to figure out the best way to say something.

“Cases that I’m not likely to mess up and cause someone to vanish?” I asked, helpfully.

“Exactly.” He nodded. “Even if you do bring Arthur down a level or two, he won’t be in serious danger, but he’s still low enough that we’ll be able to tell if you’ve made him happier. So, go over the file, make your plan, and let me know when you’re ready to leave.”

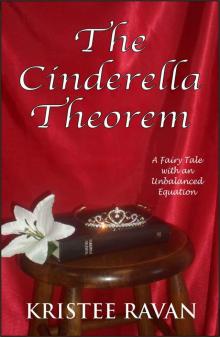

The Cinderella Theorem

The Cinderella Theorem